Bullish Risks but Bearish Developments

Five reasons oil prices have tumbled lower despite supply risks

As of late September, while we write this article, Brent and WTI crude oil prices have sank back below pre-Russian-invasion-of-Ukraine levels, with WTI trading down into the $70s after reaching $130/bbl in early March. This may come as a shock to many who had been seeing calls for crude oil to approach $140-180/bbl just a few months ago. The near 40% decline in benchmark crude futures prices from the mid-June high is admittedly a historically and statistically significant price drop in terms of both scale and duration. Not even the looming EU embargo of waterborne Russian crude oil imports supposed to go into effect in early December, Russia threatening to cut off all oil supplies to buyers that participate in the G7’s proposed oil price-cap scheme, and Russia already cutting European natural gas flows with winter approaching (which will lead to higher European gasoil demand) have been enough to sustain higher oil prices as summer draws to a close.

What’s more, these geopolitical supply risks come amid the realization of long-awaited structural supply issues stemming from years of underinvestment in new oil production outside of the U.S., leading OPEC spare crude production capacity to dwindle away to its lowest in decades. So, what could cause this steady decline in oil prices amid such an otherwise bullish risk backdrop? In this first of a 3-part article series, we will highlight the key developments in oil markets that have led oil prices lower this summer, before circling back on Russian developments in an article later this month and finally incorporating DTN winter weather, economic and oil market outlooks in November. With as many charts and as few words as possible, let us explain:

1. China’s Zero-COVID Policy

Just as the COVID-19 virus has mutated and become endemic, the impact of the virus on energy markets has evolved and proven to have long-lasting implications due to a combination of government policy responses and changes in human behavior. And when the government of the world’s largest crude oil importing nation is pursuing an extremely distinct COVID policy response than the rest of the world, the market must take notice. China’s persistent enforcement of their Zero-COVID policy, and the associated repeated lockdowns of some of the world’s largest cities this year, looks set to cause domestic refined fuel demand in China to shrink for the first time in records going back 20 years.

China has served as the backstop for oil markets for most of the last decade, operating as a sort of opportunistic buyer of last resort that would step in at times of price weakness to load up on cargoes to supply its rapidly growing oil inventory and refining capacity. It has become increasingly apparent over the past 12 months that China is no longer playing that role in global oil markets. The combination of a Zero-COVID policy and a real estate crisis brought China’s Q2 2022 GDP growth to near 0% year-on-year, youth unemployment rates skyrocketing to 20% in July, and risks the weakest yearly GDP growth since the 1970s if continued. As of mid-September, more than 65 million individuals in China were on COVID lockdown – with more Chinese cities rated at high-to-intermediate-risk according to the government tracking system than at any point since the program began in February 2020.

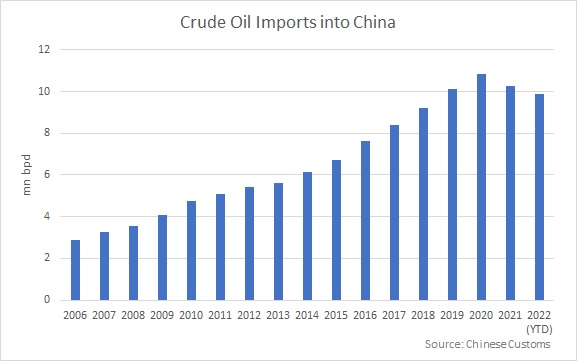

Crude Oil Imports into China

After already dropping 5.1% from 2020 levels in 2021, Chinese crude oil imports are averaging another 4.7% lower than 2021 levels so far this year. In August, according to Chinese Customs data, Chinese crude imports averaged just 9.54 million bpd – down 9.4% or 1mn bpd from the same month last year. Crude throughput at Chinese refineries fell to their lowest since March 2020 in July, and according to National Bureau of Statistics data, refinery runs have averaged an unprecedented 6.3% below year-ago levels so far this year. At a time when much of the world has been short of refining capacity, China has had the most underutilized refining capacity of any nation globally. Lower refinery utilization and export quotas in the first seven months of the year led Chinese exports of refined oil products to plummet 34% year-on-year. In the final days of September, a sizable (119 million bbls, ∼1.3 million bpd if fully realized in Q4) increase in Chinese refined fuel export quotas has reportedly been approved and is giving hope that Chinese crude demand will rebound in Q4. However, surging Q4 Chinese product exports amid a slowing global economy are likely to further weigh on global refining margins and refinery throughput elsewhere.

Hundreds of millions of people in China typically hit the roads and take domestic flights during the Mid-Autumn-Festival falling on September 10 and early October’s Golden Week holidays. This year, however, air bookings are down 40% and road congestion is expected to be down 20-30% even in non-locked-down cities as people fear being caught up in lockdowns while traveling during the holidays. While China dropping their Zero-COVID policy approach remains a major potential bullish catalyst for oil prices at some point in the future, the fact remains that China’s COVID response has caused the engine of global economic and oil demand growth to stall out so far this year.

2. Surprising Russian Export Strength

In the days immediately following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, with wide-reaching and ever-escalating sanctions announcements from the EU, UK and U.S., buyers of waterborne Russian oil dried up rapidly. The risk of being wrapped up in illegal actions and/or a public relations catastrophe led to an acute aversion to Russian barrels. This led the International Energy Agency (IEA) and many others to conclude that the global market could lose 2-3 million bpd of Russian crude oil and refined products supply by April, leading to persistent inventory draws amid an increasingly undersupplied global market. The expectation of this impending dearth of Russian supply helped lead oil prices higher through April and May, despite the fact that ship-tracking data showed exports were already rebounding as legal teams had seemingly parsed through the details and the initial sanctions-shock wore off. In fact, despite Northwest European refiners increasingly shunning Russian oil, Russian exports surged to multi-year highs in the spring as buyers in India, Malaysia (read China), Southern Europe and the Mediterranean took advantage of steep discounts for Urals crude.

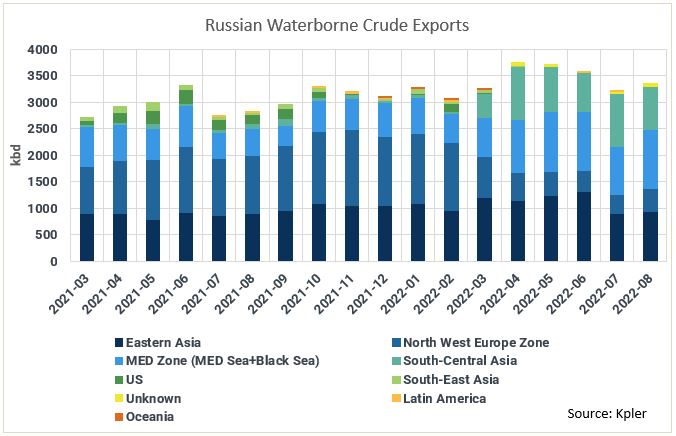

Russian Waterborne Crude Exports

In April, the IEA pushed back their Russian-supply-drop timeline, saying they didn’t expect the 3 million bpd drop to come until May. The May 15 deadline for oil trading houses to halt transactions with state-controlled Rosneft, Gazprom Neft, and Trasneft was expected to help ensure this decline. But by the time of the IEA’s May MOMR release, the agency was already pushing off their 3 million bpd Russian supply loss expectations until the second half of 2022. As European and Asian refiners continued to buy Russian oil and Russian exports continued to hold up, by June the IEA (and others) were reporting that the market had unexpectedly moved into surplus and, by their July report, concluded retrospectively that global oil inventories had been building through the second quarter. The timing of this realization nearly perfectly marked the summer-top in oil prices in mid-June.

3. Demand Destruction Denial

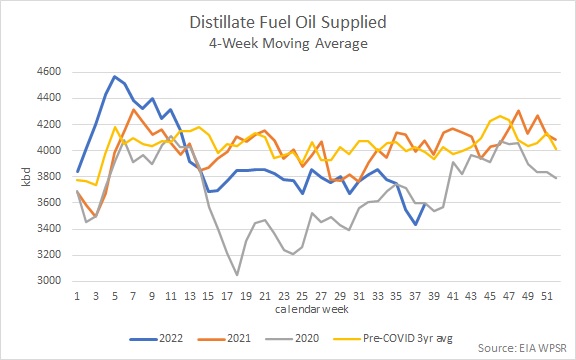

Of course, China isn’t the only nation that has seen domestic refined fuel and oil demand disappoint expectations. In the early spring of this year, U.S. diesel demand turned sharply lower, bucking the typical seasonal trend, and heralding a potential economic slowdown. Between March and mid-April, domestic demand for middle distillates fell by nearly 500,000 bpd. Given the weakness in diesel demand and the corresponding weakening trend nationally in on-road freight activity, at the time we speculated that a retail goods inventory bullwhip effect was set to shock domestic diesel demand and financial markets more broadly. What followed was a host of the nation’s largest retailers announcing on Q1 earnings calls that indeed the bullwhip effect had led to a massive backlog of retail inventories.

The combination of an abrupt halt to direct-to-consumer fiscal stimulus causing a sharp decline in inflation-adjusted incomes, consumers turning back to more service-oriented spending, and goods arriving to retailers out of season after delays at ports caused a massive backlog of inventories that slammed the brakes on freight activity and shipping demand. As a result, distillate fuel oil product supplied (the EIA’s demand proxy) fell 240,000 bpd, or 6%, short of year-ago levels in April and trailed the pre-COVID three-year average by 5%. While U.S. middle distillate demand was off to a robust first quarter, recording a 3.5% year-on-year increase, the slide in demand in Q2 left distillate fuel oil product supplied down 1.8% year-on-year in Q2, marking a 5-year seasonal low. This domestic distillate fuel oil demand weakness persisted through the summer and despite a short-lived bounce higher in August amid falling prices, demand has tumbled lower through September and currently sits 400,000 bpd below year-ago levels according to the EIA’s four-week moving average.

Distillate Fuel Oil Supplied (Four-Week Moving Average)

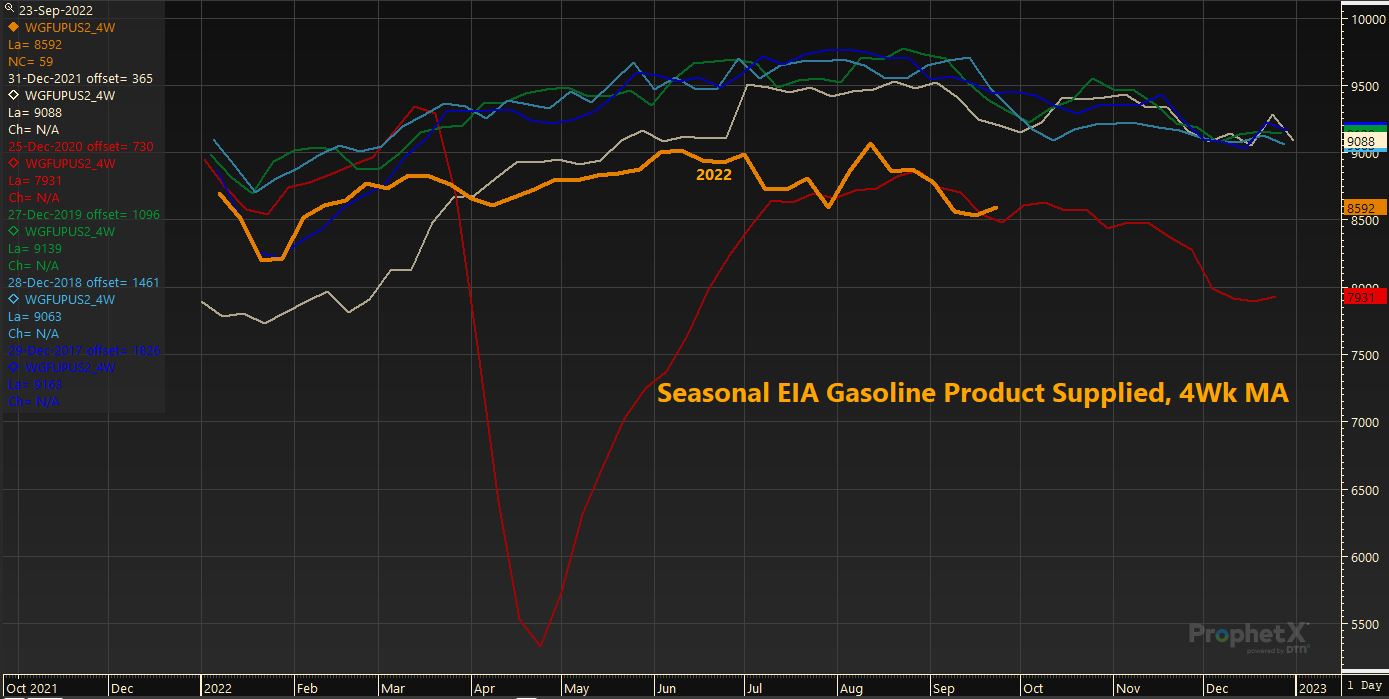

U.S. gasoline demand weakness also began to rear its head this spring amid surging gasoline prices, falling inflation-adjusted incomes and slowing economic growth. In February, gasoline product supplied was just 5% below 2019 levels and close to 10% above 2021 levels. By April, EIA data showed gasoline product supplied trending below 2021 levels, averaging 7% less than in April 2019. By early July, following weeks of record-high gasoline prices, gasoline product supplied was sharply decelerating and approaching 2020 levels for the seasonal period.

While gasoline demand had long been thought to be highly inelastic, we believe the lasting impact of COVID on consumer behavior and corporate policies like greater work from home flexibility allowed for increased consumer responsiveness to higher gas prices this summer. Gasoline demand as measured by product supplied has continued to weaken through September despite falling retail prices, as the summer driving season draws to a close. The EIA’s four-week average weekly measure is currently showing demand just 100,000 bpd above 2020 levels and 800,000 bpd below 2019 levels for the seasonal period as we enter October.

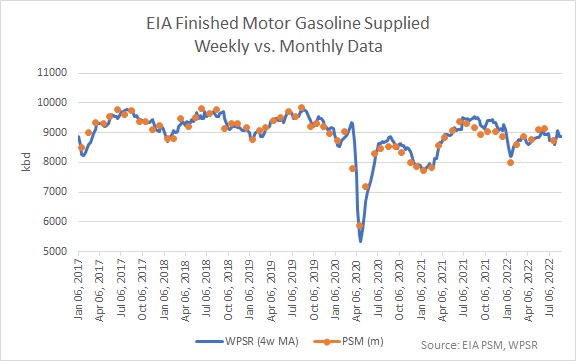

EIA Gasoline Product Supplied (Four Week Moving Average)

The EIA’s reported weakness in gasoline and diesel product supplied figures was met with skepticism by many market participants still expecting year-on-year growth and positioned for higher prices. Conspiracy theories of data manipulation or massive errors in EIA data ran amok. By early July, EIA weekly figures pointing to gasoline demand falling below 2020 levels for the seasonal period sent this speculation to a fever pitch. At this point, some investors and traders were betting that the EIA data was sending a misleadingly bearish signal by underestimating demand and that the realization of this error would ultimately send prices higher in the future.

By August, this demand destruction denial reached new heights, with Saudi Arabian Energy Minister Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman claiming to reporters that the market was in a state of schizophrenia in part because of, “unsubstantiated stories about demand destruction.” Oddly, despite AbS claiming stories of demand destruction were unsubstantiated, his proposed remedy was production cuts to tighten the market. While we recognize the timing of these claims likely had more to do with sending a signal to the West over growing hopes of a new JCPOA agreement with Iran, this statement gave those in denial about demand one last shred of hope that Saudi Arabia and OPEC would save oil prices (begging the question as to what they need saving from) by cutting output.

Although misestimations in EIA weekly figures do occur, and the EIA itself recommends using monthly data and the 4-week average for less noisy metrics, they are typically limited in duration and scale. The agency’s largest miss (when comparing monthly to weekly data) in recent history occurred last year when monthly gasoline product supplied for July 2021 was reported 367,000 bpd, or 4%, lower than their weekly figures – incidentally making this July’s weekly demand figures look relatively weaker than they should have, given that the EIA doesn’t revise their weekly figures. But by now, both EIA weekly and monthly data have revealed depressed U.S. demand over the spring and summer.

In the first half of 2022, there has been no glaring or growing error in EIA weekly gasoline and diesel demand measures relative to their monthly figures. The EIA’s monthly product supplied figures for distillate fuel oil have averaged just 13,000 bpd below their weekly reported figures and monthly gasoline data show weekly gasoline product supplied was underestimated by just 14,000 bpd in the weeklies so far this year. The latest EIA monthly data, for July, show gasoline demand averaging just 7,000 bpd below what was reported in the highly controversial weekly data at the time. Most importantly, at 8.7 million bpd in July, U.S. gasoline product supplied was down 548,000 bpd (6%) year-on-year, up only 289,000 bpd (3.4%) from July 2020 levels and down a whopping 784,000 bpd (8.2%) from 2019 levels for the month.

EIA Finished Motor Gasoline Supplied, Weekly vs. Monthly Data

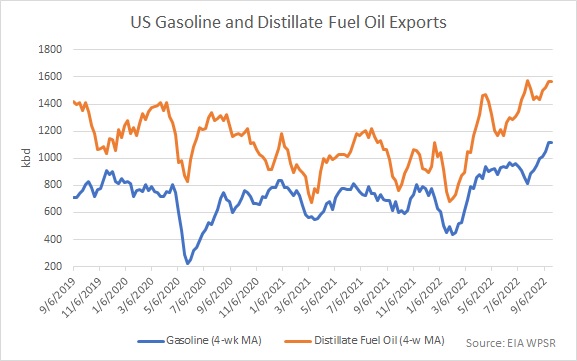

Besides many simply talking their book, one reason this denial of U.S. demand weakness persisted was because of record-strong and counter-seasonal strength in U.S. refined product exports that limited domestic inventory builds despite weak domestic demand. Even though U.S. refining capacity was down 1 million bpd year-on-year and U.S. exports had been holding at seasonal record highs since mid-April, U.S. gasoline inventories trended higher counter-seasonally from early June through mid-July. This scenario simply wouldn’t be possible without severe weakness in domestic demand. Uncoincidentally, RBOB prices and gasoline refining margins peaked for the year in the first week of June.

U.S. Gasoline and Distillate Fuel Oil Exports

4. The Toll of and Policy Response to Inflation

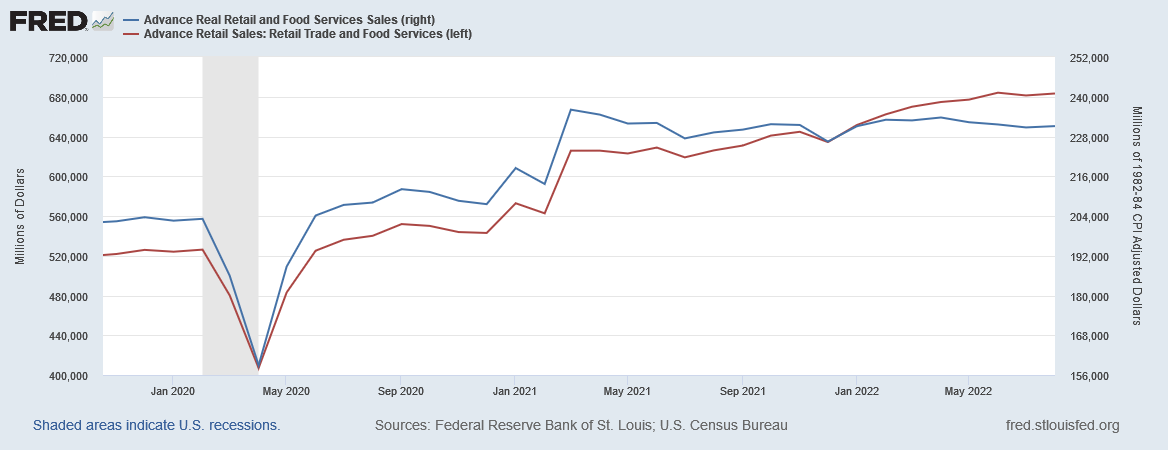

Although we all may be sick of hearing about and dealing with inflation, it ultimately remains the economic elephant in the room for almost every government, boardroom, and household. In times of high inflation, when trying to judge economic activity and the impact on oil demand, it is imperative that we think in real (inflation-adjusted) terms. After all, if activity in the supply chain and economy is measured in nominal terms (think retail sales, industrial output, e-commerce sales, household incomes etc.), the devaluation of the dollar is going to make it look as though far more economic activity is taking place than is happening in reality.

When you look at a measure like retail sales, you’re seeing a measure of the amount of dollars that exchanged hands in a month for goods, not a measure of the volume of physical goods that were moved. When thinking about oil demand in this context, it’s clear to see that what matters is the physical volume of goods being moved throughout the economy and why nominal measures can send misleadingly positive signals for oil demand in times of high inflation. We believe this strength in nominal business activity to start 2021 and lack of thinking in real, inflation-adjusted, terms gave many market participants a misleadingly optimistic view about the state of the economy and ultimately oil demand.

Real vs. Nominal Retail and Food Services Sales

As we warned last October, “The ripple effect throughout the economy caused by higher energy prices should simultaneously mean higher prices and lower output, which signals the risk of a stagflationary macroeconomic development this winter…. Energy prices truly touch every sector of the global economy. And while the old market adage that the cure for high prices is high prices, when those high prices potentially mean people are unable to heat their home or entire industries are shuttered this outlook is not much consolation.”

The Russian invasion of Ukraine led us to double down on this outlook, concluding, “The risk of a global stagflationary recession, which we already feared moving into the winter, has been greatly exacerbated as a result of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the corresponding response by governments and businesses the world over.”

Now some six months later, Europe appears to certainly be entering recession, and with the U.S. having already reported two consecutive quarterly negative real GDP prints, economists and analysts are busy debating whether the U.S. is already in a true recession or if it will come early next year. Strength in various measures of the U.S. labor market is the last vestige of optimism for those still hoping to avoid recession.

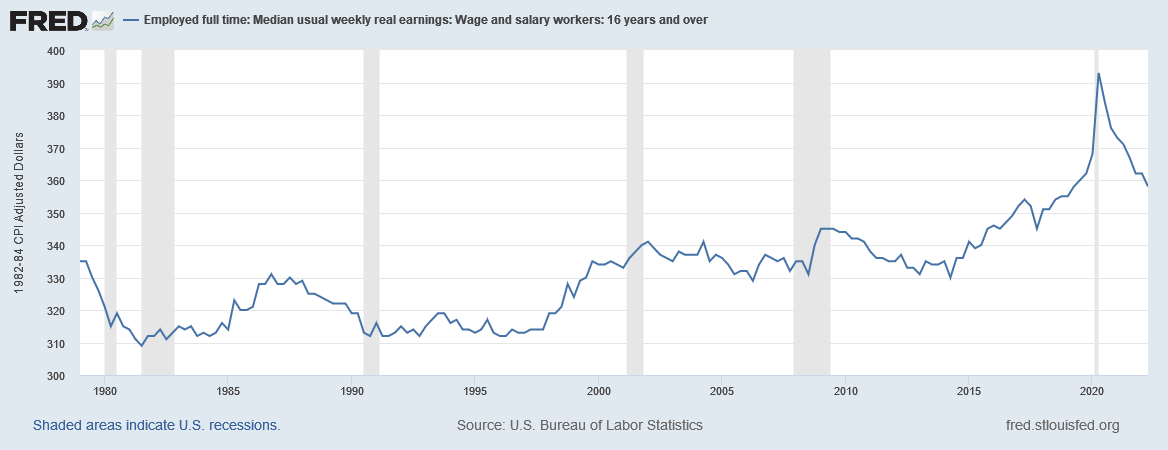

We will be the first to admit that this is no typical textbook recession or stagflation. But then again, how could it be typical amid so many seemingly once-in-a-century developments unfolding at once? Despite low unemployment as measured by U-3 and other signs of continued labor market strength, wage growth is not keeping up with inflation – leading real incomes to plummet and move below their 2015-2019 pre-COVID trend.

Median Usual Weekly Real Earnings, Wage & Salary Workers age 16+

In his August 26 speech at Jackson Hole, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell explicitly gave up on hopes of an economic “soft landing” and acknowledged that, “reducing inflation is likely to require a sustained period of below-trend growth,” and that the “pain” businesses and households would have to endure from higher interest rates was preferable to the Fed failing to get inflation under control and having to inflict even more economic pain later. It’s important to note that not only is unemployment typically a lagging indicator of recession, but the Federal Reserve is blatantly telling the market that employment is going to feel pain in due time if the Fed is to bring down inflation to their 2% target. The harsh reality is that, historically, the Federal Reserve has never been able to tame inflation above 4% without inducing a recession. And if history is a guide and inflation has truly peaked, the overwhelming odds are that the U.S. is already in a recession.

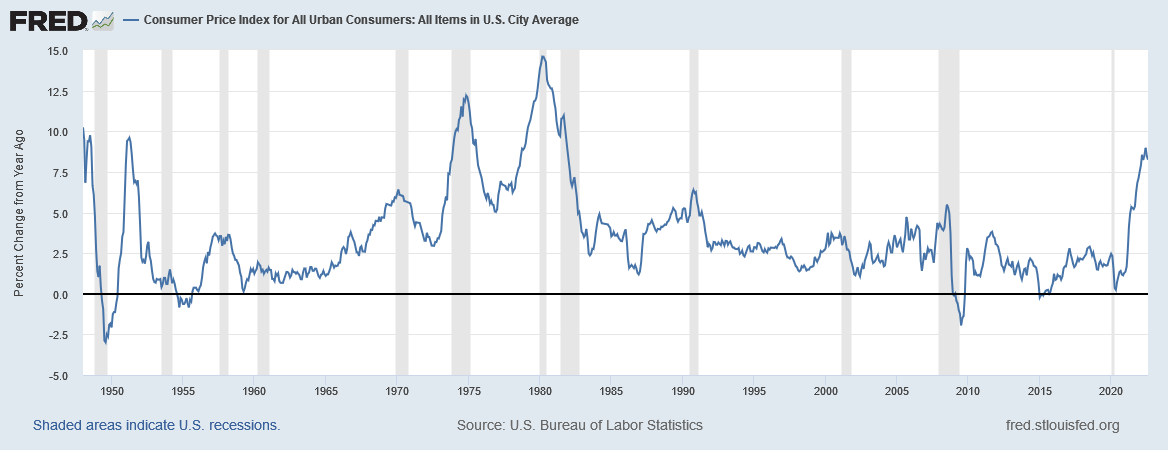

Consumer Price Index for Urban Consumers (All Items in US City Average)

A growing awareness that the U.S. and global economy aren’t holding up as well as many had hoped under the burden of inflation, in addition to knowing the lagging impacts of the Fed’s battle against inflation are still yet to be truly realized throughout the economy, is rightfully spooking oil demand outlooks and pulling oil prices lower. A recession with rising unemployment – unlike we have seen so far but that is likely necessary to tame inflation – is set to further dampen oil demand from already depressed levels. Furthermore, the Fed’s policy response to inflation, a looming recession and the unique energy supply positioning of the U.S. has meant a rapid appreciation of the U.S. dollar relative to other currencies which exacerbates demand headwinds.

5. U.S. Dollar Strength

With oil being overwhelmingly priced and traded in U.S. dollars globally, U.S. dollar appreciation is a widely known risk to oil demand. Particularly in times of already high oil prices, dollar strength amplifies costs on consumers and governments outside the United States. Said differently, currencies of the world lose oil purchasing power when the dollar is strong. A strengthening dollar therefore tends to provide pronounced headwinds for key sources of oil demand – emerging economies – that often bear the brunt of currency weakness in periods of high inflation and global economic risk. The Chinese yuan, Malaysian ringgit, Indian rupee, and many other developing economy currencies have weakened steadily against the U.S. dollar over the past year.

U.S. Dollar Index (Inverted)

But it is historic weakness in developed economy currencies like the Euro, British pound and Japanese yen that are primarily to blame for the pronounced strength in the U.S. Dollar Index over the past year. The Euro has now lost nearly 20% of its purchasing power versus the dollar since January 2021 and is trading below parity with the dollar for the first time in 20 years. Dropping to $1.03 in the final week of September, the British pound is at record lows versus the dollar. At 144 yen to the dollar, the Japanese yen is now its weakest relative to the dollar since the depths of the Asian Financial Crisis in 1998. As the IEA noted in July, “for now, weaker-than-expected oil demand growth in advanced economies and resilient Russian supply has loosened headline balances.” The sharp weakness in advanced economy currencies, as well as a rapidly depreciating Chinese yuan, versus the dollar over the past month further supports this outlook.

In Q1 2021 we published an extremely counter-consensus outlook calling for a strengthening dollar at the time. We concluded, “However, we also believe oil prices will begin moving higher alongside the dollar – bucking the typical inverse correlation – as oil demand rises through the summer. 2016 likely serves as the best possible analog for this potential scenario.” Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was not only a risk to global oil supply but simultaneously weakened the outlook for European economic activity, causing our already expected breakdown of the U.S. dollar and oil price inverse correlation to be truly obliterated. However, as global economic outlooks have deteriorated and the global oil market balance has loosened since Q2, the inverse correlation has returned.

With Europe, Japan, and China all at a relative economic disadvantage compared to the U.S. for the foreseeable future given their dependence on energy imports, and with the Federal Reserve set on taming inflation with higher interest rates pointing to further economic weakness ahead, we continue to believe the breakdown in the U.S. dollar – oil price correlation will be resolved with weaker oil prices rather than a weaker dollar.

Conclusion

Even in the early stages of a recession, oil prices can push higher. In the three recessions proceeding the COVID-19 crash of 2020, oil prices all spiked higher even though (in hindsight) the recession had already technically begun. The bullish risks remain numerous and large, and any number of event-driven scenarios like Russia cutting off pipeline supply to Europe or ceasing waterborne exports could send crude prices higher this winter. Crude oil releases from the strategic petroleum reserve should draw to a close at the end of November. The U.S. Gulf Coast still has months of Atlantic Hurricane season to go. Saudi Arabia and OPEC are almost certain to respond with production cuts (ironically lifting spare capacity) in hopes of lifting prices. The EU’s December 5th Russian waterborne crude embargo, the February 5 waterborne refined product embargo, and the risk of retaliation for participating in the G7’s Russian price cap scheme loom large. Russian oil production is in decline and OPEC spare capacity is at historic lows. However, the fact remains that despite this backdrop of known bullish risks, oil prices have tumbled lower throughout the summer well before the ultimate impact of the Fed’s monetary policy tightening has been seen on the macroeconomy.

Crude demand this autumn seems caught between the throes of a tighter diesel market due to the expected impact of lower Russian exports, lower European refinery runs and a need for gas-to-oil switching amid record natural gas prices and a sharply slowing global economy. Early insight into Q3 earnings show an economy still stuck with a massive backlog of goods inventories, new orders being slashed and the cumulative impact of months of declining inflation-adjusted incomes. FedEx, considered a bellwether for global freight, trade and economic growth, has seen its share price more than halve from its 2021 highs – plummeting nearly 40% in September alone. Waterborne container freight rates, a key indicator of global trade, are plummeting as demand slows and retail inventories brim. This does not bode well for diesel demand. And with diesel margins being the only thing keeping global refiners running as hard as they currently are, it’s easy to see how further slowing economic activity would translate into outlooks for weaker crude demand and persistent price weakness.

About the Authors

Troy Vincent

Troy Vincent is a senior energy market analyst at DTN. He worked at the Charles Koch Institute and studied at the Mises Institute while completing his Bachelor of Science in business economics and public policy from Indiana University and has been in the economic research and energy risk management industry for the past decade. Throughout that period, he has served as an analyst covering electricity, carbon dioxide, coal, natural gas, crude oil, and refined products markets. After advising companies on their energy risk management strategies while at Schneider Electric and Trane, Vincent served as a senior oil market analyst for innovative technology startup ClipperData, providing actionable intelligence for oil traders and investors. He currently specializes in crude oil, natural gas, and refined products markets; you can find his past comments and analysis across industry reports from RBN to Barron’s, MarketWatch, and Bloomberg.

Karim Bastati

Karim Bastati is a market analyst at DTN. Bastati has nearly a decade of experience in data analysis, spending the last few years in the energy industry interpreting data and building predictive models. He often acts as the central link between quantitative and qualitative research, joining an extensive knowledge of global oil markets with an analytical, numbers-oriented approach. In his previous position at ClipperData, he authored several weekly reports on crude oil and petroleum products, delivering data-derived insights.

For more market analysis, please visit DTN Energy Insights page.

Comprehensive weather insights help safeguard your operations and drive confident decisions to make everyday mining operations as safe and efficient as possible.

Comprehensive weather insights help safeguard your operations and drive confident decisions to make everyday mining operations as safe and efficient as possible.